Criminals exist in a world of perpetual motion, convinced the music will never stop. They are remarkably, almost stubbornly, blind to the inevitable conclusion of their choices. Imagine suggesting to a seasoned thief, mid-heist, that their luck is about to run out – the reaction wouldn’t be fear, but derisive laughter.

A life built on deception breeds a dangerous delusion. They become the ultimate fools, tricked by their own inflated sense of invincibility. This self-deception isn’t limited to the underworld; it afflicts faded celebrities, disgraced politicians, and even some journalists. But for those who operate outside the law, the blindness is particularly acute.

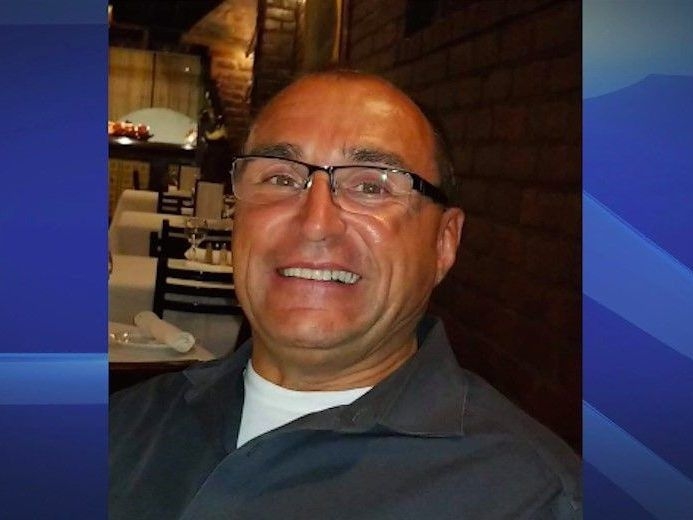

Grant Norton, a 59-year-old man who drifted through the shadows of Ingersoll, Ontario, embodied this tragic flaw. He’d spent decades skirting the edges of respectability, involved in drugs and shady dealings, always believing he could outrun the consequences. There would be no retirement, no peaceful sunset – only a brutal end.

That end came in July 2020, discovered in a chillingly casual manner: Norton’s battered body, stuffed into a white plastic barrel and discarded in the Thames River near London, Ontario. He’d been beaten and stabbed, his life extinguished after years of living on borrowed time.

Recently, the final member of the group responsible pleaded guilty to manslaughter. Wesley Peters, initially charged with first-degree murder, confessed to assaulting Norton with a firearm. The motive? A paltry $30,000. Norton was lured from his hotel room under false pretenses, subjected to a horrific ordeal, and ultimately, paid the ultimate price.

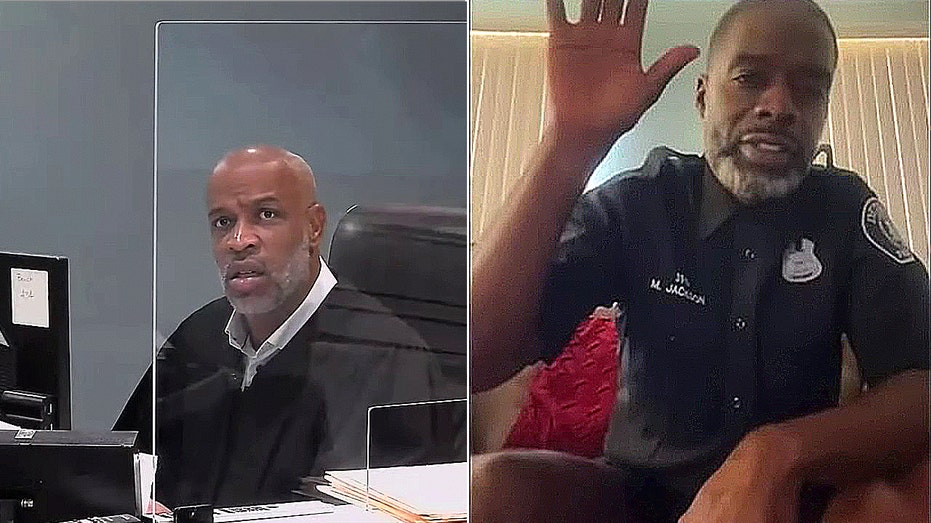

Norton’s connections to the Musitano crime family, a once-powerful organization in Hamilton, brought unwanted attention to his death. The timing – just ten days after the murder of Pasquale “Fat Pat” Musitano in a brazen public shooting – suggested a wider conflict at play. The discovery of Norton’s barrel amplified the sense of escalating violence.

Peters, burdened by guilt, reportedly confessed while in custody, seeking to alleviate his conscience. The entire operation was orchestrated by Ashley “Big Ashley” Bourget, already convicted of first-degree murder and awaiting sentencing. She’d ordered Norton’s assault, driven by a desperate need for drug money.

Three others have already been sentenced for their roles in the crime. Peters is facing an 18-year prison sentence, with credit for time served. Bourget, however, will likely spend far longer behind bars. The low-rent London gang she led is now effectively dismantled.

Grant Norton and Pat Musitano are gone, their stories concluded. While Musitano earned a place in the history of Canadian organized crime, Norton remains a footnote – a small-time crook who continued to prey on the vulnerable, even ripping off delivery drivers.

He’ll be remembered not for notoriety, but as a simple entry in the underworld’s grim accounting: another life lost, another name added to the ledger of death. A stark reminder that for those who live by the sword, the end is always closer than they think.