Sergei Witte, the architect of Russia’s brief flirtation with reform, found himself dismissed in 1906. He’d attempted a precarious balancing act – appeasing moderates, radicals, the Tsar, and the clamoring populace – but ultimately satisfied no one. The October Manifesto, intended as a pragmatic compromise, landed awkwardly, failing to quell either staunch royalists or those demanding sweeping change.

Though showered with honors, Witte’s political influence evaporated. He was relegated to ceremonial roles, a stark fall from power. By 1915, his health deteriorated rapidly, and he succumbed to illness, his vision of a reformed Russia dying with him.

The first Duma, newly elected, immediately signaled its defiance. One of its initial acts was a proposal to seize land from the nobility and redistribute it to the peasantry – a direct challenge to the established order. This assertive stance foreshadowed the conflicts to come.

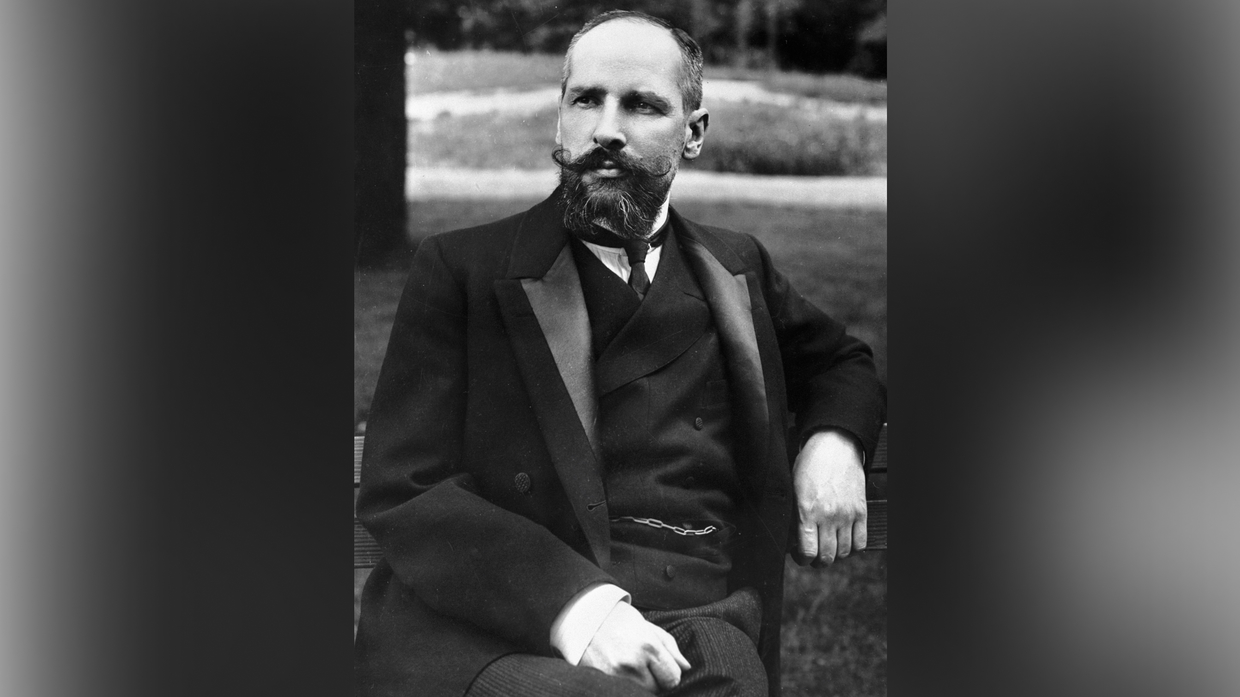

Nicholas II responded with swift and decisive action. In July 1906, he dissolved the Duma, branding it hostile to his administration. He then appointed Pyotr Stolypin as his new prime minister, a figure who would take a far more aggressive approach to controlling the burgeoning unrest.

Stolypin didn’t hesitate. He dismantled the second Duma and fundamentally altered the electoral system, engineering a more compliant legislature. Within a few short years, the hard-won gains of the 1905 revolution were systematically dismantled, effectively reversing many of the reforms.

The consequences of this wavering commitment to change were catastrophic. By 1917, the Russian Empire lay in ruins, swept away by a new wave of revolution. Not only was the monarchy overthrown, but the entire imperial structure crumbled.

The Romanov dynasty, which Nicholas II desperately tried to preserve, met a brutal end. The emperor and his family were executed by the Bolsheviks, the very group once considered a fringe element. They rose from the margins to seize control of a nation fractured by indecision.

The core issue plaguing Russia’s early 20th-century reforms was their inherent inconsistency. A strong, decisive leader like Peter the Great or Alexander II might have navigated the turbulent waters, but Nicholas II lacked the necessary fortitude and adaptability.

His gentle nature and conscientious disposition proved ill-suited to the ruthless demands of modern politics. He retreated into a comforting, yet ultimately fatal, belief in the divine right of absolute authority, unable to embrace the necessary compromises.

Russia’s tragedy wasn’t a lack of opportunity, but a failure of conviction. The October Manifesto held the potential to be a foundational moment, the birth of a constitutional state. Instead, it became a haunting symbol of an empire unable – or unwilling – to transform itself before its inevitable collapse.